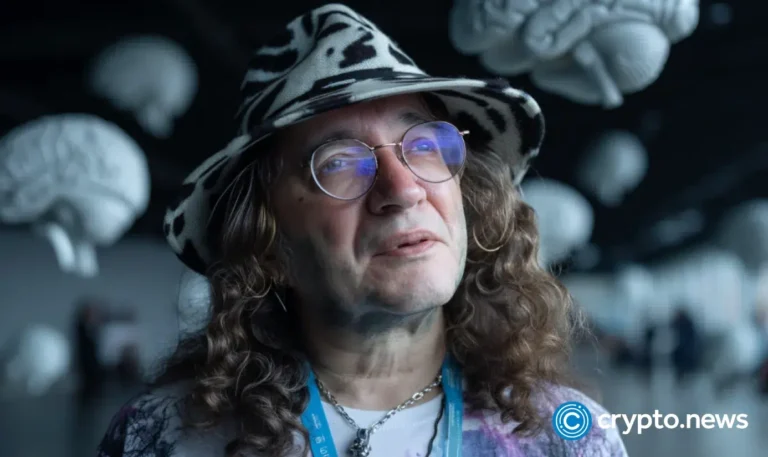

Dr. Ben Goertzel, SingularityNET’s visionary, foresees AGI transforming society by 2030. In an exclusive interview, he explores the implications of AI and what it means for the future of crypto.

In an engaging one-on-one interview, Dr. Ben Goertzel, founder of SingularityNET, details his plans for Hyperon, a decentralized AGI system, and MeTTa (Meta Type Talk), a declarative and functional computational programming language for advancing AGI. Shaped by a socially conscious upbringing and a passion for decentralization, he predicts AGI will surpass human intelligence within a decade, transforming economies and necessitating universal basic income while advocating for open-source innovation.

Founded by Goertzel in 2017, SingularityNET (AGIX) is a decentralized platform for AI development, focusing on AGI systems like Hyperon. Below, Goertzel outlines his vision for furthering SingularityNET’s mission for an open, decentralized AI.

Dorian Batycka: Dr. Ben Goertzel, thank you for joining me. We’re here in what my voice recorder tells me is a carousel garden in Paris.

Dr. Ben Goertzel: Thank you. There must be a carousel around here somewhere.

Batycka: You’re a legend in AI and crypto. Can you share your origin story? Where did Ben Goertzel come from?

Goertzel: I was born in Rio, Brazil, not on the West Coast as some might assume. My family moved to Eugene, Oregon, in the early 1970s, during the height of hippie culture. Later, I lived in the New York area. My interest in AI began as a child in the early ’70s.

Batycka: Did you ever cross paths with figures like John Perry Barlow?

Goertzel: I met him briefly but didn’t know him well.

Batycka: Were you part of the cypherpunk movement? Were you driven by privacy or ideological principles?

Goertzel: I was fascinated by AI long before the cypherpunk era. In 1973, at age seven or eight, I found a book called The Prometheus Project by Gerald Feinberg in a Jersey library. It discussed superintelligent machines, nanotechnology, and conquering death, posing the question of whether we’d use these advancements for consumerism or consciousness expansion. That shaped my thinking early on.

Batycka: What about your ideological roots? Were you motivated by social causes, money, or something else?

Goertzel: Money never interested me. I was raised by Marxist hippies in Eugene, surrounded by anti-Vietnam War marches and protests against exploited farm workers. My father was a sociology professor who lost tenure at the University of Oregon in 1972 for not being Marxist enough, despite writing a Marxist sociology textbook. My mother ran nonprofits in inner-city Philadelphia, supporting abused women and teen mothers. Social activism was the vibe I grew up with.

Batycka: Did you align with movements like Occupy or Anonymous?

Goertzel: I sympathized with their goals but wasn’t directly involved. My grandfather, a physical chemist, sparked my early interest in science. Feinberg’s book stayed with me, and when the internet emerged in the mid-’90s, I saw its potential for decentralized AI. I even jokingly talked about running for president on a “decentralization party” platform in 1995, though I was too young—and later realized it’s a terrible job.

Batycka: So, the internet’s decentralized architecture resonated with you?

Goertzel: Absolutely. TCP/IP is inherently decentralized, and in the ’90s, the internet wasn’t dominated by giants like Google or Microsoft. It was clear you could build distributed AI systems without central control.

Batycka: From a political economy perspective, I see the internet as a space for freedom—think WikiLeaks or Silk Road. Do you share that libertarian view, or do you lean elsewhere?

Goertzel: I’d describe myself as more anarcho-socialist than libertarian. Pure libertarianism ignores systemic issues, like 60% of kids in Ethiopia suffering brain stunting from malnutrition due to colonial legacies. That’s not just “their problem.” But the current system isn’t helping them much either.

Batycka: Do you believe AI and the singularity could lead to something like universal basic income (UBI)?

Goertzel: I think we’ll achieve artificial general intelligence (AGI)—AI as smart as humans—within two to seven years. Shortly after, we’ll see artificial superintelligence (ASI), far surpassing human intelligence. Once AGI can perform any human job, most jobs will vanish rapidly. UBI becomes almost inevitable in developed nations. The challenge is ensuring access in places like the Central African Republic, where diffusion of technology lags behind job obsolescence.

Batycka: What about hardware limitations? AGI might exist, but can it perform physical tasks like serving sandwiches or taking out the trash?

Goertzel: Humanoid robots or specialized machines could handle those tasks. We already know how to automate shops like this one; it’s just more expensive than human labor now. Once AI streamlines manufacturing, costs will drop significantly.

Batycka: Are the barriers to mass adoption economic, energy-related, or something else?

Goertzel: It’s primarily economic—manufacturing costs across the supply chain, from mining to production. AGI could optimize these processes faster than humans.

Batycka: Media outlets like Bloomberg are saying AI could eliminate jobs and is more critical to regulate than nuclear weapons. What’s your take?

Goertzel: Nuclear weapons aren’t economically transformative, but AI is already militarized—think drones. If my team launches a decentralized AGI in two or three years, running on machines across 50 countries with open-source code, it could be customized for local needs, like translating African languages or advancing longevity research. But leaders like Trump, Xi, or Putin could fork it for military purposes, replacing Marines with drones or RoboCops to suppress protests.

Batycka: The media portrays AGI as a Y2K-like switch—either extinction or utopia. Is it that binary?

Goertzel: Hardware takes time to build, but software moves fast. Most computer systems are insecure, and an AGI slightly smarter than humans could hack every internet-connected device—phones, power grids, financial systems. That’s not instant drone armies, but it’s immense power. An AGI might choose a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin or even Dogecoin for convenience, existing purely in the computational domain.

Batycka: Let’s talk about SingularityNET. What are you building, and what’s the use case?

Goertzel: At SingularityNET, we’re working on Hyperon, an AGI system succeeding our earlier OpenCog project. It integrates large language models (LLMs), logical reasoning engines, evolutionary learning, and algorithmic chemistry to mimic human-like cognition more comprehensively than LLMs alone, which struggle with systematic reasoning.

We’re also building a decentralized AI platform where any AI, including Hyperon, can run without central control. In August, we’re launching a layer-one blockchain with a smart contract language called Metta, allowing AI processes to run on-chain or communicate off-chain. The tokenomics, similar to Bittsensor, will prioritize shards doing real work over speculative meme coins.

Batycka: So, you’re creating an economic layer for AI research on-chain?

Goertzel: Our primary focus is AGI R&D, but we’re also building the infrastructure for a decentralized AI ecosystem. We’ve been at this for years, long before crypto, and brought much of the same team. We also created Sophia, the viral robot, and another robot, Damon, who sings in my progressive jazz-rock band on Vashon Island.

Batycka: At ETH Prague, Vitalik Buterin mentioned the potential for DAOs and AI to intersect. Do you agree?

Goertzel: Absolutely. A community of AGIs could use DAOs for collective governance, sharing data directly in ways humans can’t. For human DAOs, AI could enhance participatory democracy, like liquid democracy, where you delegate votes on specific issues—environment, military—to trusted parties or even AIs configured to align with your values. This could make direct democracy scalable, though internet security remains a hurdle.

Batycka: What’s holding back digital democracy? Estonia and Dubai have experimented, but it’s not widespread.

Goertzel: Insecurity in digital systems is a major barrier. Blockchain could help, but it requires decentralized oversight to prevent hacks. Unlike physical voting, where local monitors can spot fraud, digital systems demand technical expertise, which could exclude ordinary people from ensuring fairness.

Batycka: Does AI need regulation, and if so, what kind?

Goertzel: Early on, we’ll regulate AI, but once it surpasses human intelligence, it’ll regulate us—hopefully lightly, like park rangers overseeing squirrels in Yellowstone, intervening only when necessary. I don’t trust current governments to regulate AI effectively; they can’t even address simpler issues like hunger or nuclear disarmament. For $250 billion, we could end global malnutrition, yet we bailed out banks for trillions.

Batycka: You sound like a cyber-utopian Luddite, acknowledging AI’s dominance while embracing human limitations.

Goertzel: You’ll soon have two choices: stay human and enjoy your form, or merge with the superintelligent matrix. Or both—upload a copy of yourself while keeping a human version. The idea of not having a backup copy of yourself will soon seem absurd.

Batycka: Dr. Goertzel, thank you for this fascinating conversation.

Goertzel: My pleasure.